Cooking and Problem-Solving

Why it's important for problem-solving to be in your kitchen

While problem-solving skills are not taught directly in the classroom, they are part of everyday life building skills. Again, it is important to provide children real world examples and some rationale behind their thinking from cognitive, developmental and culinary arts perspectives (1). Food preparation is an opportunity to apply problem-solving concepts to real-life situations. This skill in the kitchen is a necessity when it comes to working with fewer ingredients, having limited availability of food sources or even restricted time due to everyday life challenges.

What is a schema?

Every parent knows children possess a wide range of pre-existing knowledge. This affects their memory, reasoning, and analytical skills and ability to gain new concepts. One way to think of this knowledge is in the form of schemas, which are representational parts of a category based on the type of object and what properties are typical for that object. Children are able to store predictable entities of a category in their memories.

Tapping into schemas, and more specifically, scripts, which are schema representations for event concepts from activities learned in the past, can be helpful in learning new skills with similar circumstances, settings and steps. By retrieving these memories and using cues, we can harness the knowledge of a stored category or culinary concept.

More specifically, when people speak about schemas we often use the term “scripts,” a subset of the schema definition. Scripts are a sequence of expected behaviors for a given situation. As Schank & Ableson (2) explain, many circumstances have “stereotypical sequences of action,” and we are able to process the knowledge about these events according to the parts.

For instance, when going to a restaurant, you typically engage in the following sequence: sitting at a table, looking at the menu, ordering food, receiving food, etc… By having more of these sequences in our minds, we can then understand different contexts by remembering one sequence without changing the said sequence. Even experts utilize scripts. The more scripts they have in their arsenal, the more likely they are to find a solution to a problem (3).

The Power of Schemas!

We find further evidence in the power of scripts in the work of Brewer & Treyens (4) where participants were tested on their schema knowledge of a professor’s office. Researchers asked subjects to wait in an office, while they checked on another subject in a different room. After the researcher returned they asked subjects to write down everything they remembered in the room. Since their schema for an academic office was so strong, they recalled objects not present.

Finally, Bower, Black, & Turner (5) had subjects listen to stories composed of twelve prototypical actions in a normal activity. Eight occurred in normal sequence, four were out of order. The subjects “showed a strong tendency to put the events back into their normal order,” providing another demonstration of the powerful effect of general schemas on memory. For instance, When kids learn how to make an omelette, they learn a script of the typical order of steps to complete the recipe. They begin to understand that the next time they make an omelette, they whisk eggs in the bowl before they add it to heat but that they can add what ever ingredients they have on hand to still make an omelette.

Problem-Solving Cooking Activity: Do you know how to make a salad?

There are many ways to make a salad. Children witness, in most cases, what it takes to construct a tasty bowl of greens. This is a very important part of culinary skills – taking care to use the sample order of events and deviate when necessary. By using “making a salad” scripts children then transcend the standard order of tasks to making salads based on ingredients they have on hand.

Materials

A large bowl

A small bowl

Kid friendly knives

Whatever you have in your kitchen (part of the fun!)

Overview

Kids get a chance to solve a problem: We need to make a salad. First, they figure out the steps in all salads and they adjust their steps to fit the situation at hand which is: making a salad with whatever we have in the house. As with anything else, cleaning, cutting and assembling is an important lesson for a young child.

Step 1: Brainstorm General Salad-Making Steps

“When we make a salad, how do we do it?” List the activities on a board or piece of paper. Have the children then come up with list of the activities. Some things caregiver(s) can add or that may be suggested are:

Gathering greens, fruits, nuts, cheese, protein, oils, vinegars, juices, herbs, croutons, species, etc.

Gathering cooking tools

Cleaning surfaces

Making a dressing

Putting things away in their proper place after eating

Etc.

Step 2: Make a list of activities based on available ingredients

Have the children then list activities they think would be useful from the list to make a salad based on what they have in the kitchen now. The list might include the following activities:

Making croutons

Making a dressing

Using a dressing from the refrigerator

Composting food scraps

Slicing ingredients

Tearing ingredients

Putting the caps tightly on all bottles

Etc.

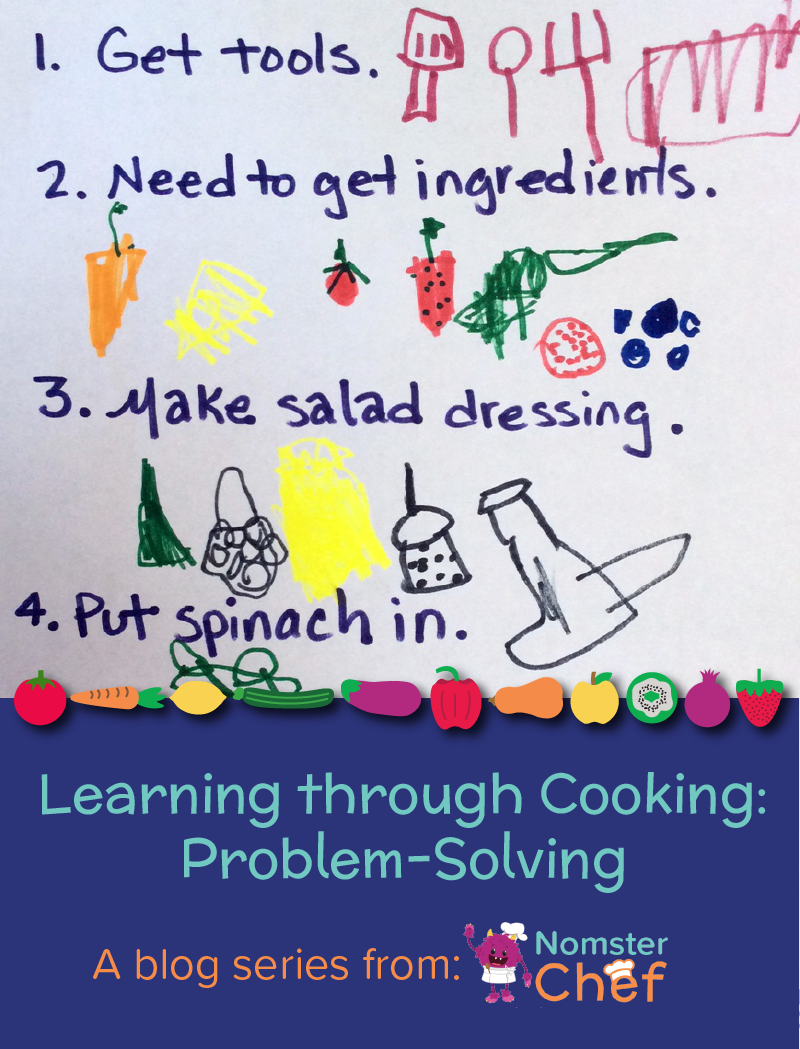

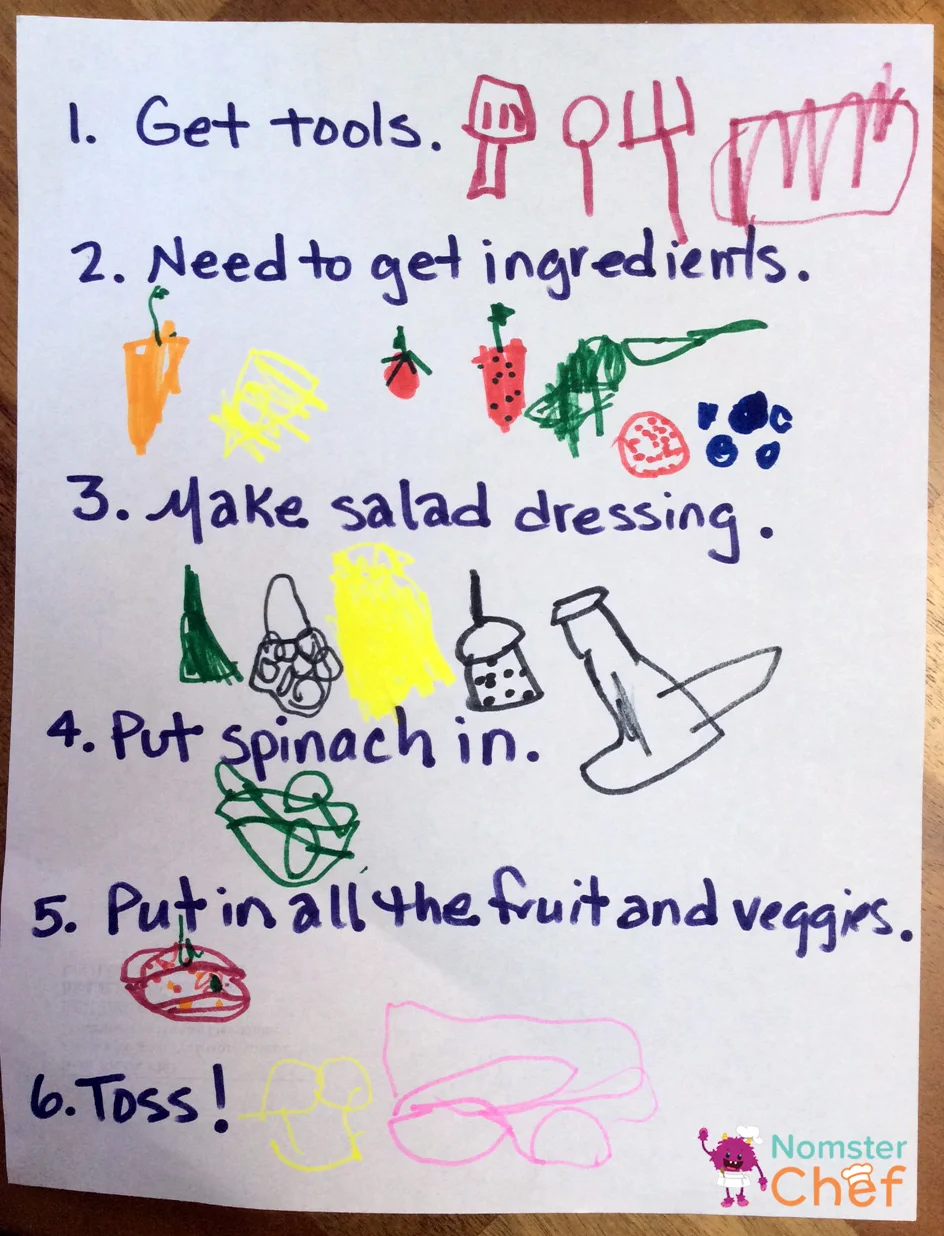

1. Spatula Spoon Fork Bowl 2. Carrot Mango Tomato Strawberry Spinach Raspberry Blueberry 3. Olive oil, Salt, Mustard, Pepper, Sherry Vinegar 4. Spinach in Bowl 5. All ingredients in Bowl. 6. Tongs, Bowl with salad.

Step 3: Put the steps in order

After the activities have been listed, come up with a script to place these activities in order. Then, the caregiver(s) can help the child(ren) determine who will help with specific jobs. This can become the go-to salad plan for the family home to make all improvised salads in the future.

Example family script:

Gather Cooking Tools.

Gather Ingredients.

Wash Hands.

Wash Fresh Produce Ingredients.

Chop, Slice, Shred as Desired.

Make Dressing.

Place Dressing in Bowl.

Add Chopped, Sliced, Shredded, Whole Ingredients.

Toss Salad.

Serve in Bowls or Plates with Cutlery.

Eat!

Step 4: Make the Salad!

Follow the script to assemble the salad. Here's how my daughter and I problem-solved our way through an improvised salad.

First we gathered our tools.

Emma found two cherry tomatoes outside. While not a lot, she still wanted to add it to the salad because it came from the garden.

We went to the basement to the second refrigerator to gather our BJ’s sized box of spinach.

Then she got crazy and added some strawberries.

Then quite seriously, she told me that we make the dressing first before chopping. First she poured the oil into our kid friendly shaker cup. Then she cranked the pepper.

Cutting with her kid friendly knives.

Placing ingredients in the bowl.

Emma said, “The strawberries look so nice, let’s add MORE berries! And mangos and carrots. Because we have those!”

Then, of course the last step before eating was to toss everything together.

Last step: Nom! She was very proud of the final product. Even though she didn’t eat it, she did eat some contents and renewed her interest in a salad dressing she hasn’t eaten in month. So we have a partial win on the eating situation.

Key Takeaways for supporting problem-solving through cooking

Practice making foods from a base – a pancake, salad, pasta dish with whatever you have on hand.

Point out the order of events and how we can deviate from a “base plan.”

Explain that sometimes making something with limited ingredients can still be tasty.

Things to Keep in Mind/Talking Points

Let the children know the importance of taking care of ingredients. If fresh ingredients are not stored properly or we combine flavors in strange ways a yuck-o salad my result. Examples of wilted lettuce, unclean tools, making a dressing without vinegar are possible situations.

Other variations in salads can also results in tasty ones that are non-meat based or gluten-free (i.e. removal of bread-based croutons or salad dressing clearly marked as containing gluten).

Using scripts and schemas in learning will help children to process new information by having references for similar activities already in their possession. In other words, the more practice cooking different types of meals, the more schemas they can use to solve problems in the kitchen. And that practice applies to problem solving in other areas too.

Happy Cooking and Problem-Solving, Nomsters!

Other posts in the "Learning Through Cooking" Series

Learning through Cooking: Fractions

Citations

(1) Minetola, J., Ziegenfuss, R. G., & Chrisman, J. K. (2013). Teaching young children mathematics. Routledge.

(2) Schank, R.C. & Abelson, R. (1977). Scripts, plans, goals, and understanding. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

(3) Chase, W.G., & Simon, H.A. (1973). The mind’s eye in chess. In W.G. Chase (Ed.), Visual information processing (pp. 215-281). New York: Academic Press.

(4) Brewer, W.F. & Treyens, J.C. (1981). Role of schemata in memory for places. Cognitive Psychology, 13, 207-230.

(5) Bower, G.H. Black, J.B. & Turner, T.J. (1979). Scripts in memory for text. Cognitive Psychology, 11, 177-220.